Tête-à-Tête 2: Interview with Alan Reid

March 7th, 2013 – MATTHEW BOURBON

The Chameleon

Alan Reid was one of my first students when I arrived to teach at the University of North Texas. Since he graduated, many years ago, we have continued to talk, follow each other’s art, debate over some minor formal quirk in a 19th century painting and occasionally eat a meal together. With his upcoming exhibition at Lisa Cooley, I decided to ask him my ten Tête-à-Tête questions. As per usual Alan took the task to heart.

Alan Reid was born in 1976 in Texas and currently lives and works in New York. He holds degrees from the University of North Texas and the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland. Recent exhibitions include A Pallazzo, Brescia; Mary Mary, Glasgow; Galerie Jacky Strenz, Frankfurt; Talbot Rice, Edinburgh; and Keno Twins 5, curated by Michael Bauer at Barriera, Torino. He curated the exhibition Air de Pied-a-terre for Lisa Cooley in January 2013 and will have a solo show at the gallery in April 2013. Reid will be included in the second edition of Phaidon’s “Vitamin D.”

Matthew Bourbon: What are you currently working on (or recently finished) in your studio?

Alan Reid: The question for me is whether to allow oneself to be comforted by articulation, one’s own or in reading the world. Poetically, the studio allows for an eruption of a particular force; I like the word “grace,” despite its complicated etymology—to thank, or Greek “graces,” or the Christian “grace”? Is grace bestowed or our thankful response? In the studio, I’m following passions (sometimes horribly faint), contending with the impossibility of emergence and the question of how to articulate. Maybe it’s my taste, I‘m simply motivated by the emotional feedback that is working on painting. This means, of course, that I might be compared to Renoir, or something ridiculous, leaning into the anachronism, but who cares? To present something to one’s raw self is a gift. So much of life is patching a persona that asking oneself, are you happy with this color, seems a radical act.

There’s a part of me that sees the work as building a capacity to love, which means acceptance of the appearance of love in all its weirdness. Quaint, I know. Of late, my loves have been very formal: surface, equivalence, harmony, ambiguity, foreignness. All this is about being in close proximity. Do you know the W. Benjamin line about aura, being distance, close at hand? I’ve thought about lightness for years and could write a solid syllabus that would begin with a close reading of Calvino’s “Six Memo’s for the New Millennium” and Kundera’s “Unbearable Lightness of Being.”

The beginning and end of work isn’t something I deal with very consciously. Seems the set of behaviors constituting art making is never current, finished or fixed. Things are picked up and put down again. Materials lead the way and are fought. I look for ways to interject. Notice a sense of being at war with oneself?

Studio logic is abstract; it’s a method to reconcile contradictions, both wild-panicked urge to relay content and indifference appear equal. I always think about the Fitzgerald line (was it Amory in “This Side of Paradise”? I hear both words “amour” and “aimless” echoed in his name) that goes something like, “intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

Before we move from the topic of the studio, I wanted to share the ridiculous conclusion I’ve come to: The studio’s god is Hermes. It’s a messenger workshop. Right? Like diligence organizes an observation of the nature of transmission…dispatched to the gods, or oligarchs, or academics is beside the point: The locus is the mechanics of messaging.

Anyway, I’m putting together my fifth solo show, third in NY at Lisa Cooley, which is called POEMS: Sans Souci. I think the show might be about all this I’m blathering on about, a sense of something carefree bumping into the heaviness of poetic ambition. The roots of the word “insouciance” grow from the term “sans souci,” you know!

Reason to Love

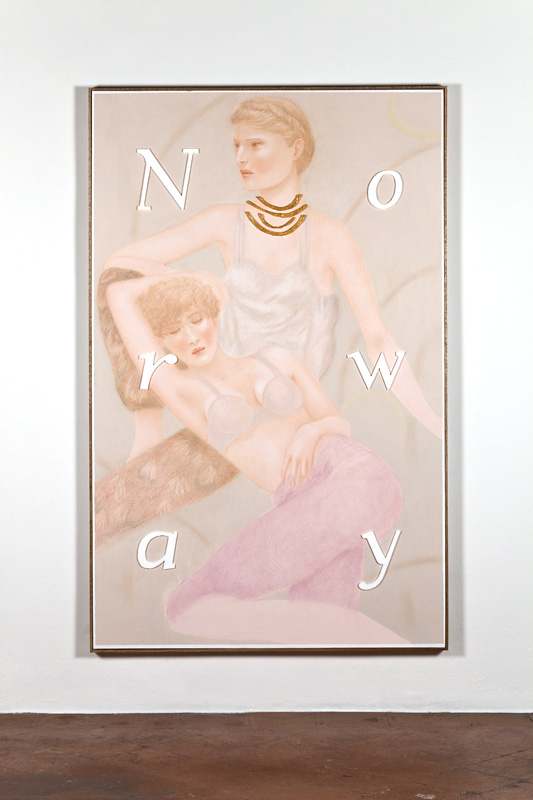

But then as soon as I say this, I have to readdress the show, because it’s equally about reading, which reoccurs to me with every move. “Read” defined as “interpret.” In this show, I’m thinking specifically about reading music. I’m making a series of paintings with composers’ names as an entry point. Sannsouci, Frederick the Great’s palace, is a literal, historical site we can point to, where the arrival of Baroque chamber music for a moment eclipsed the visual arts. He pulled in Haydn and Bach, etc. to write for the place, to my mind at the expense of visual art, but maybe this is a fanciful reading. I like the idea that visual art’s irrelevance is a subplot. On one level, these are portraits of nouns; I like the romance of the composers’ names. The graphic style is eclectic and all over, Ikko Tanaka to Old English. I’m in the midst of these, so it’s too early to give a full account. I do notice a series of concerns, unrelated to the names, demanding to take precedence—as if the drive to create is too dense for the object in front of me. I’ll also show some Caran d’ache images of women. I’ve been making these for several years now. The longer I work on this set, the less I understand. But I find them beautiful. The process is pleasant and the range of negotiation they demand is still fascinating.

A Weekend Befogged

MB: Who do you consider your visual art kin?

AR: I feel pressure from the world: influencing, seducing, what to love and how to shape that love. I’m realizing many of the analytical tools useful in excavating meaning come from within the work. I think about Matisse surrendering to pleasure. Brancusi’s elegant overthrow of high culture with his idea of primitive. Mondrian and syncopation. Pierre Klossowski for weaving together reading and looking; I have a fondness for painters who write (Duchamp and Bridget Riley, an odd couple, have been on my mind lately). I love extreme superficiality: Arp for shapes, Albers for colors and Ryman for whites. But ultimately, art kin are for students. One has to leave history and find the living. My friend Matthew Brannon is pretty fucking good. I feel something for Enrico David’s splintered way of showing psychic tension and Lucy McKenzie’s provocations couched in tradition. And I love the gallery I show with here in New York. My colleagues at Lisa Cooley continually present brightness. Of course there is a constant pang knowing we leave all of this, the tinsel of our milieu, to become dust. I find solace in Agnes Martin for bravely reaching out, but she won’t be stemming any tides.

Matthew Brannon

MB: What things, outside of other visual artists, influence your art?

AR: Essays haunt me. I find my reflection in films. And music is a constant companion. It’s weird, now entering middle age (oh fuck) I still completely surrender to music. I bore Jenny [Alan’s companion] constantly with philosophic interjections—talking forever about insignificant minutiae. Sounds in the studio run the gamut: German synth (Moritz von Oswald!) to roots reggae, post-punk, Japanese sound experiments, house, Liszt. We’re such a prolific musical culture, multi-sided, deep and experimental. But in the context of my adoration of music, I recognize a deep distrust of industry motives, and an ever-present vision of a vast ethical immaturity in pop, so I hope for higher forms. But I love pop. I made a painting last year called Disco Lyrics, which is about this, I think. There’s a thin line between nothing and something.

Then there is all the unaccounted for impressions and half-formed interests. For years, I’ve been looking at the J. Crew catalogues regularly arriving by mail. They show up like orphans. I’ve used them for stylistic things: lighting, color, etc. But I’ve started to see them as the universe handing me a problem: What is this pleasant, inoffensive, casual but assured projection of humanity? I can’t find good precedence of someone working with this notion, so it’s become an obsession. To isolate so I can see it, to name and define. It’s not just J. Crew, of course, it’s everywhere—perfect masks promising steady emotion. Persona perfection. I thought I should take this in, to adopt the orphan… why not? But this notion filtered through my craftwork, just drawing them out, making it up as I go, doing a little shading, feeling my way around—well, it makes the whole enterprise inexplicable. There’s an avalanche of dumb questions that follow. Like, what is the subject supposed to wear? What are they vending? This has caused me to study up on fashion, which no one seems to find amusing except me. Sometimes I think the work is like Medusa, existing to just stop me cold, to calcify. Freud said Medusa is an image of castration.

A Reckless Affair

MB: What is your studio practice like—can you describe the process of making your work?

AR: Moving stuff around while I worry, panic, am bemused, enter a fog, am indifferent, feel joy, talk to the cats. When solutions finally come, I’m elated for 45 minutes and then a dour sense of “who cares” sets in. Probably, all art is mining for significance.

I’ve been trying to expand the ways I make things, so there are no rules. I’m fortunate in that I basically work in the studio all day, looking for a plan, but the problem-solving urge gets in the way so I have to work against myself.

Generally, I’m looking for density, which has meant pulling disciplines into each other. My favorite works have exhaustion in common. In the later stages, there’s a drain of mental and emotional store. When there’s nothing left to lose, I think, “Well, I might as well try to make primitive panties and put them on that woman’s head.” It’s very cathartic to act out this sort of behavior, which I don’t understand.

MB: What questions, subjects or concerns drive your current work?

AR: The nature of appearance is the work, so I guess questions rise from what and how things appear. Thoughts developed out of the air. Right now I’m thinking about visual harmony, which is infinitely complicated to arrest, and specifically harmony between text and image. I’ll help…it doesn’t exist. But ideas occur in a form! They’re brought in a certain basket, and set in front of us.

MB: What are some of the challenges you encounter in the making of your art?

AR: Boredom. Poverty. Criticality getting between me and enjoyment. A monkish tendency to endure discomfort for the work. The awareness that art is solitary.

Really the only true challenge is removing satisfaction from the production equation. The work has a way of tying up loose ends eventually; one just cannot expect to find satisfaction in the result. With no expectation, everything that arrives is a kind of miracle.

MB: What’s your favorite film? Why?

AR: I should mention an Antonioni here, but maybe simply conjuring his name will give me the bravery to campaign for the modest Le Collectionuse, because our desires are infinitely complicated and Rohmer does a fine job conveying the way hunger looks from the outside and what it sounds like in conversation, among his sect. I’ve been blown over by European cinema for a million years. Among the many compelling attributes, I’m interested in the way a certain type of woman protagonist appeared with the rise of the auteur theory; she often provides a voice to masculine auteur concerns: Godard/Karina, Antonioni/Vitti, Bergman/Ullmann, Chabrol/Audran, et al. Through their process, the subject presented seems deeply hermaphroditic, arguably a more whole human?

Monica Vitti

The directors I mentioned seem particularly concerned with the expression of anima. Anyway, I see myself playing with this idea, both directly in the work (my emotion, drawn in someone else’s facial expression) and indirectly, by providing stumbling blocks for the galleries (strange all the galleries I’ve worked with have been spearheaded by females). As example, I recently titled an innocuous work To Come at the Same Time. Imagine this said professionally. But the joke rings on, because the work really is founded on mutual jouissance, contracted between viewer and work. Maybe I think the work is simply a prop? But I’ve already said too much.

MB: What are you reading right now? How does your reading affect what you do in the studio?

AR: You would ask this. Our readers should know our friendship is nearing its fifteen year anniversary! Our conversations have encouraged me for years. And the topics have been films, books, music, art… these are THE categories. The gospels.

Auden! I’m not sure why I was so slow to approach, but I’m enjoying my late arrival. He has a fascinating ability to command raw nature to anthropomorphize in countless ways, and he’s a great shifter of time, tone and tense. Plus there’s that constant, lead-heavy awareness of brevity—the currency of poetry? “The grave proves the child ephemeral.” Maybe, reading affects the studio by providing an ideal audience.

MB: Can you describe one of your favorite pieces that you have made and why you think it is important to your larger body of work?

AR: My favorites are not my own. I like the works others like. They have become useful.

MB: What are you working on next?

AR: I’m attempting to write a catalogue essay for a forthcoming publication on Matthew Brannon; it’s proving to be less the essay and more an experiment. And fancying a stab at writing something for myself. Perhaps on Disco Lyrics?

Disco Lyrics

Or maybe I’ll write something on vowels? I’ve been playing with vowels, beginning last year with a work called Consecutive Vowels…basically a long string of letters adhered to a wall that, when read, sounds like someone having an orgasm. The thing culminates in a series of “oui, oui, oui” (so it can’t be confused with the sound of dying). After the initial pun I started to think, the appearance of vowel sounds in our spoken repertoire happens at a very primitive point in our lives. Seems when we’re babies we vocalize these soft sounds first and work our way toward complication. At the atomic level of words, vowels glue clustered consonants together (every word retains our child utterances). Once I saw the vowels as primitive, I thought it was appropriate they should appear medieval, reflecting the Gutenberg era; dawn of printing. But this is another story.

Matthew Bourbon is an artist and writer. His paintings have been shown nationally and internationally. In our neck of the woods, his work was included in the Texas Biennial, New American Paintings and in Tender Pioneers at Darke Gallery in Houston. He is currently an associate professor of art at the University of North Texas’s College of Visual Arts and Design. Bourbon also contributes to Art Forum Online, Flash Art, ArtNews, New York Arts Magazine and KERA Art and Seek.